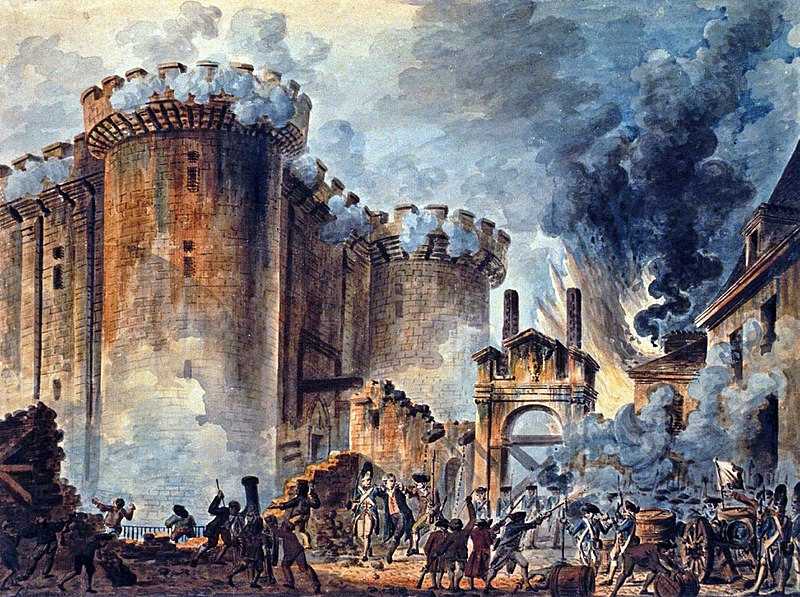

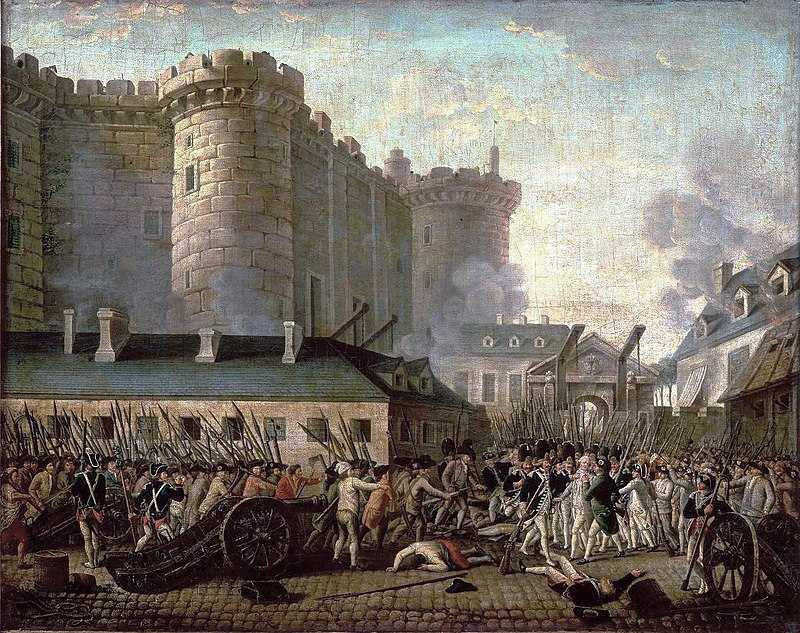

Storming of the Bastille

The Storming of the Bastille (French: Prise de la Bastille [pʁiz də la bastij]) occurred in Paris, France, on the afternoon of 14 July 1789. The medieval fortress, armory, and political prison in Paris known as the Bastille represented royal authority in the centre of Paris. The prison contained just seven inmates at the time of its storming, but was seen by the revolutionaries as a symbol of the monarchy's abuses of power; its fall was the flashpoint of the French Revolution.

In France, Le quatorze juillet (14 July) is a public holiday, usually called Bastille Day in English

Storming the Bastille (14 July 1789)

On the morning of 14 July 1789, the city of Paris was in a state of alarm. The partisans of the Third Estate in France, now under the control of the Bourgeois Militia of Paris (soon to become Revolutionary France's National Guard), had earlier stormed the Hôtel des Invalides without meeting significant opposition. Their intention had been to gather the weapons held there (29,000 to 32,000 muskets, but without powder or shot). The commandant at the Invalides had in the previous few days taken the precaution of transferring 250 barrels of gunpowder to the Bastille for safer storage.

At this point, the Bastille was nearly empty, housing only seven prisoners: four forgers, two "lunatics" and one "deviant" aristocrat, the Comte de Solages (the Marquis de Sade had been transferred out ten days earlier).

The high cost of maintaining a garrisoned medieval fortress, for what was seen as having a limited purpose, had led to a decision being made shortly before the disturbances began to replace it with an open public space. Amid the tensions of July 1789, the building remained as a symbol of royal tyranny.

The regular garrison consisted of 82 invalides (veteran soldiers no longer suitable for service in the field). It had however been reinforced on 7 July by 32 grenadiers of the Swiss Salis-Samade Regiment from the regular troops on the Champ de Mars. The walls mounted 18 eight-pound guns and 12 smaller pieces. The governor was Bernard-René de Launay, son of the previous governor and actually born within the Bastille.

The official list of vainqueurs de la Bastille (conquerors of the Bastille) subsequently compiled has 954 names, and the total of the crowd was probably fewer than one thousand. A breakdown of occupations included in the list indicates that the majority were local artisans, together with some regular army deserters and a few distinctive categories such as 21 wine merchants.

The crowd gathered outside around mid-morning, calling for the surrender of the prison, the removal of the cannon and the release of the arms and gunpowder. Two representatives of the crowd outside were invited into the fortress and negotiations began, and another was admitted around noon with definite demands. The negotiations dragged on while the crowd grew and became impatient. Around 1:30, the crowd surged into the undefended outer courtyard. A small party climbed onto the roof of a building next to the gate to the inner courtyard and broke the chains on the drawbridge, crushing one vainqueur as it fell. Soldiers of the garrison called to the people to withdraw but in the noise and confusion these shouts were misinterpreted as encouragement to enter. Gunfire began, apparently spontaneously, turning the crowd into a mob. The crowd seems to have felt that they had been intentionally drawn into a trap and the fighting became more violent and intense, while attempts by deputies to organise a cease-fire were ignored by the attackers.

The firing continued, and after 3:00 pm, the attackers were reinforced by mutinous gardes françaises, along with two cannons. A substantial force of Royal Army troops encamped on the Champ de Mars did not intervene. With the possibility of mutual carnage suddenly apparent, Governor de Launay ordered a cease-fire at 5:00 pm. A letter offering his terms was handed out to the besiegers through a gap in the inner gate. His demands were refused, but de Launay nonetheless capitulated, as he realised that with limited food stocks and no water supply his troops could not hold out much longer. He accordingly opened the gates to the inner courtyard, and the vainqueurs swept in to liberate the fortress at 5:30.

Ninety-eight attackers and one defender had died in the actual fighting, a disparity accounted for by the protection provided to the garrison by the fortress walls. De Launay was seized and dragged towards the Hôtel de Ville in a storm of abuse. Outside the Hôtel, a discussion as to his fate began. The badly beaten de Launay shouted "Enough! Let me die!"and kicked a pastry cook named Dulait in the groin. De Launay was then stabbed repeatedly and died. An English traveller, Doctor Edward Rigby, reported what he saw, "[We] perceived two bloody heads raised on pikes, which were said to be the heads of the Marquis de Launay, Governor of the Bastille, and of Monsieur Flesselles, Prévôt des Marchands. It was a chilling and a horrid sight! ... Shocked and disgusted at this scene, [we] retired immediately from the streets."

The three officers of the permanent Bastille garrison were also killed by the crowd; surviving police reports detail their wounds and clothing.

Two of the invalides of the garrison were lynched, but all but two of the Swiss regulars of the Salis-Samade Regiment were protected by the French Guards and eventually released to return to their regiment. Their officer, Lieutenant Louis de Flue, wrote a detailed report on the defense of the Bastille, which was incorporated in the logbook of the Salis-Samade and has survived. It is (perhaps unfairly) critical of the dead Marquis de Launay, whom de Flue accuses of weak and indecisive leadership. The blame for the fall of the Bastille would rather appear to lie with the inertia of the commanders of the 5,000 Royal Army troops encamped on the Champ de Mars, who did not act when either the nearby Hôtel des Invalides or the Bastille were attacked.

Returning to the Hôtel de Ville, the mob accused the prévôt dès marchands (roughly, mayor) Jacques de Flesselles of treachery, and he was assassinated en route to an ostensible trial at the Palais-Royal.

The king first learned of the storming only the next morning through the Duke of La Rochefoucauld. "Is it a revolt?" asked Louis XVI. The duke replied: "No sire, it's not a revolt; it's a revolution."

At Versailles, the Assembly remained ignorant of most of the Paris events, but eminently aware that Marshal de Broglie stood on the brink of unleashing a pro-Royalist coup to force the Assembly to adopt the order of 23 June and then to dissolve. The vicomte de Noailles apparently first brought reasonably accurate news of the Paris events to Versailles. M. Ganilh and Bancal-des-Issarts, dispatched to the Hôtel de Ville, confirmed his report.

By the morning of 15 July, the outcome appeared clear to the king as well, and he and his military commanders backed down. The Royal troops concentrated around Paris dispersed to their frontier garrisons. The Marquis de la Fayette took up command of the National Guard at Paris; Jean-Sylvain Bailly – leader of the Third Estate and instigator of the Tennis Court Oath – became the city's mayor under a new governmental structure known as the Commune de Paris. The king announced that he would recall Necker and return from Versailles to Paris; on 17 July, in Paris, he accepted a tricolour cockade from Bailly and entered the Hôtel de Ville to cries of "Long live the King" and "Long live the Nation".

0 comments

Sign in or create a free account