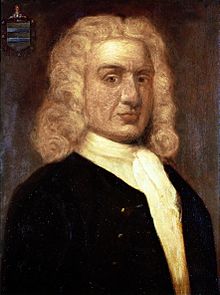

William "Captain" Kidd

William Kidd, also known as Captain William Kidd or simply Captain Kidd (c. 1655 – 23 May 1701), was a Scottish sailor who was tried and executed for piracy after returning from a voyage to the Indian Ocean. Some modern historians, for example Sir Cornelius Neale Dalton, deem his piratical reputation unjust.

Biography

Early life and education

Kidd was born in Dundee, Scotland. Greenock was given as his place of birth (although some say it was Dundee, and others say Belfast), and his age as 41 in testimony under oath at the High Court of the Admiralty in October 1694 or 1695. A local society supported the family financially after the death of the father. The myth that his "father was thought to have been a Church of Scotland minister" has been discounted, insofar as there is no mention of the name in comprehensive Church of Scotland records for the period. Others still hold the contrary view.

Early voyages

Kidd later settled in the newly anglicized New York City, where he befriended many prominent colonial citizens, including three governors. Some published information suggests that he was a seaman's apprentice on a pirate ship during this time, before partaking in his more famous seagoing exploits.

By 1689, Kidd was a member of a French–English pirate crew sailing the Caribbean under Captain Jean Fantin. During one of their voyages, Kidd and other crew members mutinied, ousting the captain and sailing to the British colony of Nevis. There they renamed the ship Blessed William, and Kidd became captain either as a result of election by the ship's crew, or by appointment of Christopher Codrington, governor of the island of Nevis. Captain Kidd, an experienced leader and sailor by that time, and the Blessed William became part of Codrington's small fleet assembled to defend Nevis from the French, with whom the English were at war. The governor did not pay the sailors for their defensive services, telling them instead to take their pay from the French. Kidd and his men attacked the French island of Marie-Galante, destroying its only town and looting the area, and gathering for themselves around 2,000 pounds sterling. Later, during the War of the Grand Alliance, on commissions from the provinces of New York and Massachusetts Bay, Kidd captured an enemy privateer off the New England coast. Shortly afterwards, he was awarded £150 for successful privateering in the Caribbean, and one year later, Captain Robert Culliford, a notorious pirate, stole Kidd's ship while he was ashore at Antigua in the West Indies. In 1695, William III of England appointed Richard Coote, 1st Earl of Bellomont, governor in place of the corrupt Benjamin Fletcher, who was known for accepting bribes to allow illegal trading of pirate loot. In New York City, Kidd was active in the building of Trinity Church, New York.

On 16 May 1691, Kidd married Sarah Bradley Cox Oort, an English woman in her early twenties, who had already been twice widowed and was one of the wealthiest women in New York, largely because of her inheritance from her first husband.

Preparing his expedition

On 11 December 1695, Bellomont was governing New York, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire, and he asked the "trusty and well beloved Captain Kidd" to attack Thomas Tew, John Ireland, Thomas Wake, William Maze, and all others who associated themselves with pirates, along with any enemy French ships. It would have been viewed as disloyalty to the crown to turn down this request, carrying much social stigma, making it difficult for Kidd to say no. The request preceded the voyage which established Kidd's reputation as a pirate and marked his image in history and folklore.

Four-fifths of the cost for the venture was paid for by noble lords, who were among the most powerful men in England: the Earl of Orford, the Baron of Romney, the Duke of Shrewsbury, and Sir John Somers. Kidd was presented with a letter of marque, signed personally by King William III of England. This letter reserved 10% of the loot for the Crown, and Henry Gilbert's The Book of Pirates suggests that the King may have fronted some of the money for the voyage himself. Kidd and his acquaintance Colonel Robert Livingston orchestrated the whole plan; they sought additional funding from a merchant named Sir Richard Blackham. Kidd also had to sell his ship Antigua to raise funds.

The new ship, Adventure Galley, was well suited to the task of catching pirates, weighing over 284 tons burthen and equipped with 34 cannon, oars, and 150 men. The oars were a key advantage, as they enabled Adventure Galley to manoeuvre in a battle when the winds had calmed and other ships were dead in the water. Kidd took pride in personally selecting the crew, choosing only those whom he deemed to be the best and most loyal officers.

Because of Kidd's refusal to salute, the Navy vessel's captain retaliated by pressing much of Kidd's crew into naval service, despite rampant protests. Thus short-handed, Kidd sailed for New York City, capturing a French vessel en route (which was legal under the terms of his commission). To make up for the lack of officers, Kidd picked up replacement crew in New York, the vast majority of whom were known and hardened criminals, some undoubtedly former pirates.

Among Kidd's officers was his quartermaster Hendrick van der Heul. The quartermaster was considered "second in command" to the captain in pirate culture of this era. It is not clear, however, if van der Heul exercised this degree of responsibility because Kidd was nominally a privateer. Van der Heul is also noteworthy because he may have been African or of African descent. A contemporary source describes him as a "small black Man". If van der Heul was indeed of African ancestry, this fact would make him the highest-ranking black pirate so far identified. Van der Heul went on to become a master's mate on a merchant vessel and was never convicted of piracy.

Mythology and legend

The belief that Kidd had left buried treasure contributed considerably to the growth of his legend. The 1701 broadside song "Captain Kid's Farewell to the Seas, or, the Famous Pirate's Lament" lists "Two hundred bars of gold, and rix dollars manifold, we seized uncontrolled". This belief made its contributions to literature in Edgar Allan Poe's "The Gold-Bug"; Washington Irving's "The Devil and Tom Walker"; Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island and Nelson DeMille's Plum Island. It also gave impetus to the constant treasure hunts conducted on Oak Island in Nova Scotia; in Suffolk County, Long Island in New York where Gardiner's Island is located; Charles Island in Milford, Connecticut; the Thimble Islands in Connecticut; Cockenoe Island in Westport, Connecticut; and on the island of Grand Manan in the Bay of Fundy.

Captain Kidd did bury a small cache of treasure on Gardiners Island in a spot known as Cherry Tree Field; however, it was removed by Governor Bellomont and sent to England to be used as evidence against Kidd.

Kidd also visited Block Island around 1699, where he was supplied by Mrs. Mercy (Sands) Raymond, daughter of the mariner James Sands. The story has it that, for her hospitality, Mrs. Raymond was bid to hold out her apron, into which Kidd threw gold and jewels until it was full. After her husband Joshua Raymond died, Mercy moved with her family to northern New London, Connecticut (later Montville), where she bought much land. The Raymond family was thus said to have been "enriched by the apron".

On Grand Manan in the Bay of Fundy, as early as 1875, reference was made to searches on the west side of the island for treasure allegedly buried by Kidd during his time as a privateer. For nearly 200 years, this remote area of the island has been called "Money Cove".

In 1983, Cork Graham and Richard Knight went looking for Captain Kidd's buried treasure off the Vietnamese island of Phú Quốc. Knight and Graham were caught, convicted of illegally landing on Vietnamese territory, and assessed each a $10,000 fine. They were imprisoned for 11 months until they paid the fine.

0 comments

Sign in or create a free account