Marie François Sadi Carnot

Marie François Sadi Carnot (11 August 1837 – 25 June 1894) was a French statesman, who served as the President of France from 1887 until his assassination in 1894.

Early life

Marie François was the son of the statesman Hippolyte Carnot and was born in Limoges, Haute-Vienne. His third given name Sadi was in honour of his uncle Nicolas Léonard Sadi Carnot, a pioneer in the study of thermodynamics, named after the famed Persian poet Sadi of Shiraz. Like his uncle, Marie François too came to be known as Sadi Carnot. In his scientific-mindedness and Republican leanings, he resembled his grandfather, Lazare Carnot, the military modernizer and member of the post-Revolutionary French Directory. Marie François was educated as a civil engineer and was a highly distinguished student at both the École Polytechnique and the École des Ponts et Chaussées. After his academic course, he obtained an appointment in the public service. His hereditary republicanism caused the government of national defence to entrust him in 1870 with the task of organizing resistance in the départements of the Eure, Calvados and Seine-Inférieure, and he was made prefect of Seine-Inférieure in January 1871. In the following month he was elected to the French National Assembly by the département Côte-d'Or. He joined the Opportunist Republican parliamentary group, Gauche républicaine. In August 1878 he was appointed secretary to the minister of public works. He became minister in September 1880 and again in April 1885, moving almost immediately to the ministry of finance, which post he held under both the Ferry and the Freycinet administrations until December 1886.

Presidency

When the Daniel Wilson scandals occasioned the downfall of Jules Grévy in December 1887, Carnot's reputation for integrity made him a candidate for the presidency, and he obtained the support of Georges Clemenceau and many others, so that he was elected by 616 votes out of 827. He assumed office at a critical period, when the republic was all but openly attacked by General Boulanger.

President Carnot's ostensible part during this agitation was confined to augmenting his popularity by well-timed appearances on public occasions, which gained credit for the presidency and the republic. When, early in 1889, Boulanger was finally driven into exile, it fell to Carnot to appear as head of the state on two occasions of special interest, the celebration of the centenary of the French Revolution in 1889 and the opening of the Paris Exhibition of the same year. The success of both was regarded as a popular ratification of the republic, and though continually harassed by the formation and dissolution of ephemeral ministries, by socialist outbreaks, and the beginnings of anti-Semitism, Carnot had only one serious crisis to surmount, the Panama scandals of 1892, which, if they greatly damaged the prestige of the state, increased the respect felt for its head, against whose integrity none could breathe a word.

Carnot was in favour of the Franco-Russian Alliance and received the Order of St Andrew from Alexander III.

Death

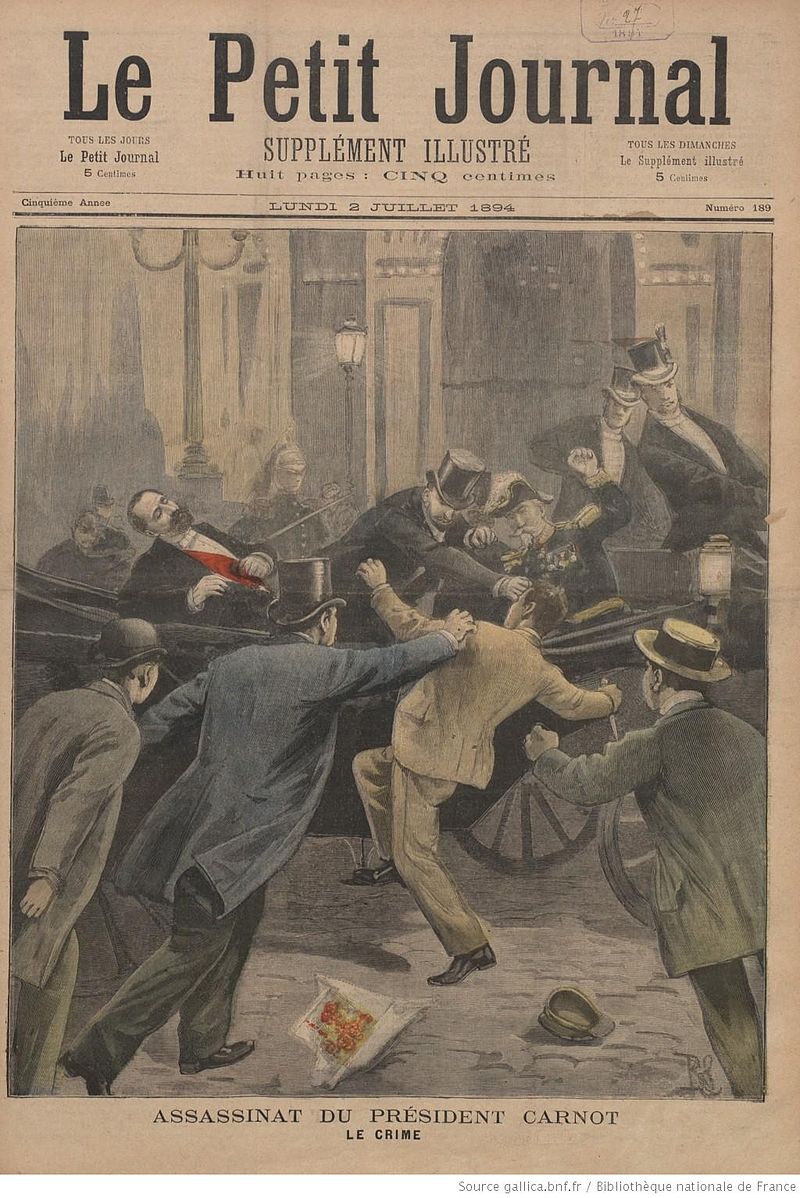

Carnot was reaching the zenith of his popularity, when, on 24 June 1894, after delivering a speech at a public banquet in Lyon in which he appeared to imply that he would not seek re-election, he was stabbed by an Italian anarchist named Sante Geronimo Caserio. Carnot died shortly after midnight on 25 June. The stabbing aroused widespread horror and grief, and the president was honoured with an elaborate funeral ceremony in the Panthéon on 1 July 1894.

Caserio called the assassination a political act, and was executed on 16 August 1894.

0 comments

Sign in or create a free account