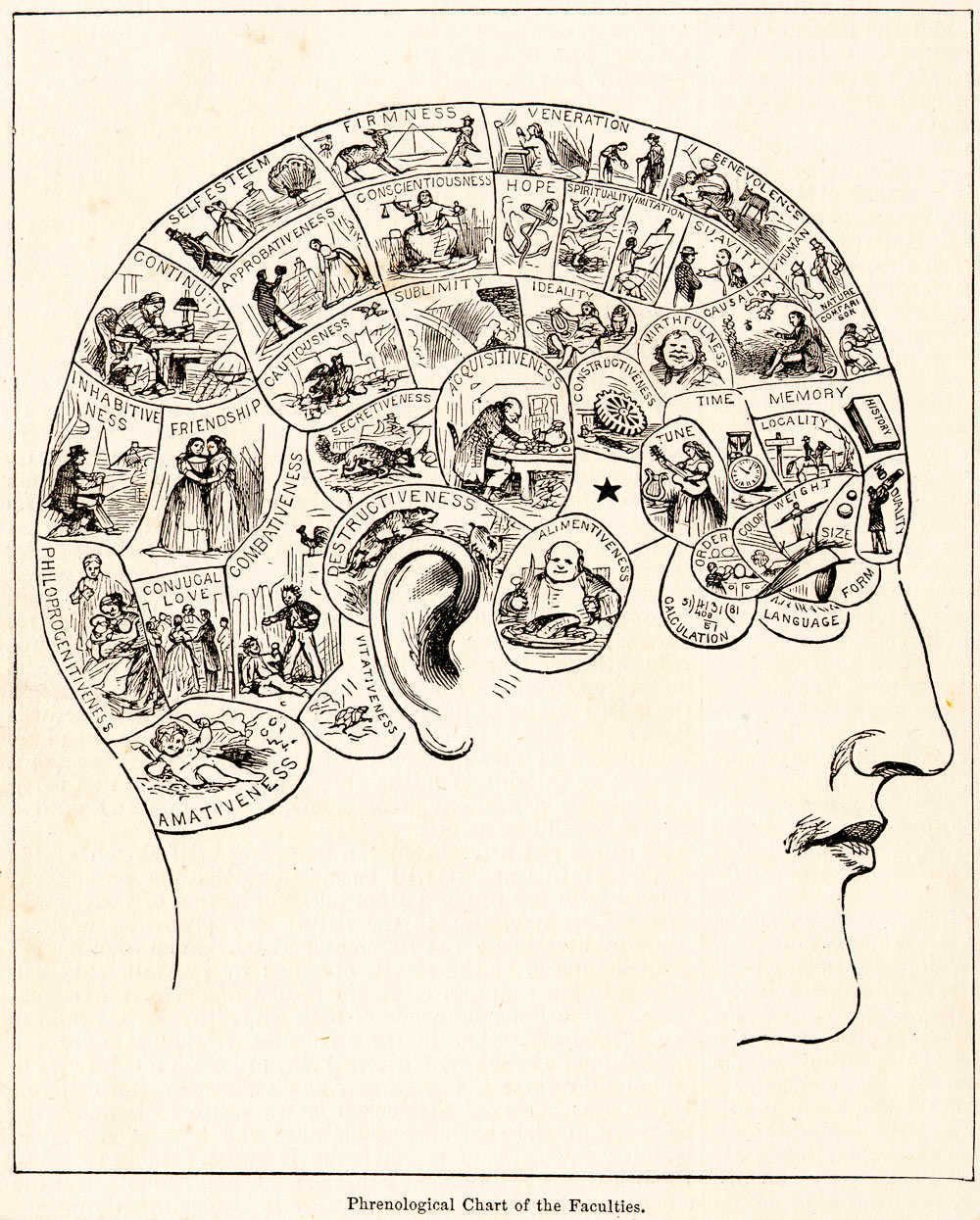

Phrenology

Phrenology illustrates how psychological theory—in this case, one that emphasizes individual differences—orients discourses and research about the brain.

Based on the theories of the Viennese physician Franz Joseph Gall (1758–1828), who called it “organology” and “doctrine of the skull” (Schädellehre), phrenology assumed that the brain is the organ of the mind; that the mind is composed of innate faculties; that each faculty, from amativeness and benevolence to secretiveness and wit, has its own brain “organ” (twenty-seven in Gall’s original scheme); that the size of each organ is proportional to the strength of the corresponding faculty and that the brain is shaped by their differential growth; and, finally, that since the skull owes its form to the underlying brain, its “bumps” reveal psychological aptitudes and tendencies. Phrenology and the accompanying practices of cranioscopy and cranial palpation remained hugely popular into the 1840s, and phrenological publications appeared steadily until after World War I.

Gall (1835, 1:55) noted that “as the organs and their localities can be determined by observation only, it is also necessary that the form of the head or cranium should represent, in most cases, the form of the brain, and should suggest various means to ascertain the fundamental qualities and faculties, and seat of their organs.” The deductive form of his claim points to the lack of empirical connection between organology and brain research. Yet Gall, together with his disciple Johann-Caspar Spurzheim (1776–1832), carried out significant neuroanatomical investigations, innovated in dissection methods, contributed to demonstrations that the nerves stem from gray matter, and described the origins of several cranial nerves (Rawlings and Rossitch 1994, Simpson 2005). All of this, however, had no empirical connection to their phrenological localizations.

0 comments

Sign in or create a free account